She started calligraphy when she was a child and saw her grandfather’s back. She became familiar with calligraphy at an early age, and has worked her way up to become a calligrapher of this era, while learning deeply about the history of letters and the origins of calligraphy. Her quest has been to express with her own brush the timeless beauty that has been handed down through the ages, using her masterful calligraphy techniques. This is not to handle letters in a self-indulgent and free manner, but to respect the aesthetic and spirituality of calligraphy, which has been cultivated over a long period of time. She does not stop at mastering the writing method. She also has an insight into the meaning of the expressive qualities of the ‘Yohaku(margins)’, for example, and the ideas contained in the relationship with Japanese culture. What are the realisations she has gained while immersing herself in the world of calligraphy, and what are her thoughts on creation of calligraphy? Mariko Kinoshita talks about the essence and appeal of calligraphy.

Q: Why did you decide to take up calligraphy?

When I was a child, my parents were both working and I was often left at my grandfather’s house. My grandfather had the custom of having me Rinsho (The practice of copying ancient calligraphic masterpieces) every morning, using the classics as a model. I saw his back figure silently working at his desk in the room with the morning sun shining in, and it looked so dazzling. I think that scene was burned into my eyes. I later inhterited my grandfather’s handbooks (125 volumes of “Shoseki Meihin Soukan”, famous calligraphy works in Japan and China, published by Nigensha). I still use it with great care.

Q: Has your attitude to calligraphy changed between when you first started and now?

At school or in a local calligraphy class, we learn the standard and running scripts that we are used to seeing, and that’s the end of the normal learning process. However, Kanji characters started with seal script, which inscriptions on oracle bone used by the Shang dynasty in China more than 3,000 years ago, and progressed through official script, cursive script and running script before arriving at the regular script. This is known as the “five Chinese character scripts”, and a common misconception is that the line and cursive scripts were formed by a breakdown of the standard script. However, the Kai style is the most recent typeface, having been completed at the end of the Kai style. In this way, the essence of calligraphy is to come into contact with characters in the context of their historical background and history, and to explore the aesthetic and spirituality contained in the original forms of characters and calligraphy. I became aware of this when, as a university student, I went to Liandao Island in the Yellow Sea, China, to see the Liandao Boundary Engraving Stones, which were engraved some 2,000 years ago. It was a bad day with strong wind and rain, and the weathering over the years was so severe that it was difficult to read the inscriptions, but I was very moved by them. I could still feel the breath of the people who once carved on the rock face from the letters that had been left behind. I realised then that this was something worth pursuing for the rest of my life.

Q: Is it necessary to know the history of writing to understand calligraphy?

Considering that kanji characters were originally formed to represent the shapes of things and to indicate their meanings, distorting the letterforms of the characters in one’s own way or exaggerating them too much would also make the meaning of the characters strange. There is also a pattern for how to distort the characters in f lowing kana. In recent years, letters written with an impact in the modern sense of design have been called “brush letter art”, but this is completely different from “Traditional calligraphy art”. I believe that characters that have been shaped and refined over a long period of time, through the accumulation of many people’s handwriting, are already works of art in their own right.

Q: Tell us about the process of establishing your ‘identity’ as a calligrapher

The culture and ideas that form the basis of our current way of living and thinking come from the West after the Meiji Restoration, and are different from the culture and ideas that have been nurtured in Japan since ancient times. In terms of ideology, the difference is between ‘man conquers nature’ and ‘man is part of nature’. The Japanese people’s once modest spirituality is reflected in Japanese culture, particularly in the calligraphy of the kana syllabary, in the aesthetic sense of loving the crumbling fragility, imperfection and asymmetry of things rather than strength and perfection. The calligraphy of those who were known as “Nousho(excellent calligrapher)”, as a part of Japanese culture, did not push “individuality” and “self-expression” to the fore, as is the case in the West. If you learn a lot from such predecessors and the ancient way of life, and sublimate what you have learnt in your own mind, it will come out in your calligraphy without you having to be particularly conscious of it. This is what I think about in my daily life when I come into contact with ancient calligraphy.

Q: What do you think is the Japanese national character as seen through calligraphy?

During the Great East Japan Earthquake, the Kesennuma Bay area in Miyagi Prefecture was severely damaged by the tsunami. I was very impressed by the story of a fisherman who runs an oyster farming business there, and even though he was in awe of nature’s fury, he spoke of his appreciation of the bounty of nature, accepting it rather than resenting it. Such a view of nature was held in the hearts of the Japanese people in the past, and I believe that this DNA has been passed on deep down in their hearts, even if they are not aware of it. I think that Japanese modes and architecture, which have developed around the world, also contain not a little of this spirituality, and I think that in the international ecological orientation of recent years, there is much to be learnt from ancient Japanese ideas and concepts.

Q: Have there been any difficulties in continuing to write?

I think it is really a blessing to be able to continue doing one thing for so long. But of course there are times when you hit a wall, and when that happens, there is something that comes to mind for me. San’u Aoyama, a teacher I respect, is known for never having held a solo exhibition in his life. However, after he passed away, the Tokyo National Museum held a major exhibition of his work, but as to why he did not hold a solo exhibition, he seemed to think that calligraphy is something you learn and improve throughout your life, and it would be embarrassing to do so in the middle of it. I also remember a comment he made to me when I met Seikaku Takagi, the leading kana (Japanese syllabary) master. He said, “In modern times, I spend far less time with a brush than I did in the past, so it would take two hundred years of my life to reach the level of Nousho of the Heian period. In other words, being aware that you are always ‘incomplete’ is the driving force that keeps you going, isn’t it?

Q: What has been the most memorable event in your life as a calligrapher?

In 2020, I was able to write on the stage at the Noh theatre adjacent to Kasuga Taisha shrine, which is related to the Fujiwara clan, at a ceremony organised by Nara Prefecture to commemorate the 1,300th anniversary of the compilation of the Chronicles of Japan. The Chronicles of Japan, Japan’s first official history based on imperial instructions, is basically written in Chinese, and as a student of the classics, it was a great honour for me to be able to do so. Nara Prefecture is one of Japan’s leading ink-producing regions, and I was deeply moved and impressed by the fact that I was provided with ink and inkstones from the long-established Kobaien ink shop, as well as water from the Ohmiwa Jinja Shrine at my request, so that I could polish the ink and write the calligraphy.

Q: Are there any calligraphers or artists who have influenced you?

I mentioned San’u Aoyama, who was a great influence on me. When I was choosing a university to go to, the fact that he taught there was a reason for my choice. Unfortunately, he had passed away by the time I entered the university, but after entering, I met my teacher, Seiu Takaki, who was a beloved disciple of teacher Aoyama, and I have been studying under him ever since. I have been a teacher for all these years, and my teacher is so important that your whole life depends on which teacher you study under. In that sense, I think I was lucky. Now I am in the generation between the masters and the young students. Just as all of my teachers have been good teachers as well as players, I am not only exploring my own calligraphy, but I am also working on the educational side at the same time, passing on what I have learnt to the next generation.

Q: Which do you feel is more important, calligraphy technique or sensitivity?

Both are important. In calligraphy, it is important not only to learn by hand, but also by eye, and in the classroom we not only learn to write (to cultivate the senses of the hand), but also to look at calligraphy (to cultivate the eye), to read calligraphy (to learn from the past) and to write (to learn from the past). The instructors also teach calligraphy so that students can acquire a good sense of the art of calligraphy at the same time through ‘looking at calligraphy’ (cultivating the hand), ‘reading calligraphy’ (learning from the past) and ‘talking about calligraphy’ (understanding its charms) .

Q: How do you relate to calligraphy in your daily life?

In modern society, we are exposed to a lot of unnecessary information, so I try to stay away from that in my calligraphy, and work without going against the natural order of things, while keeping my mind in order. Recently, there is a term called ‘time performance’ (taipa), and I try to spend time slowly and carefully when I am writing. I also try to keep beautiful paintings and calligraphies, or photographs that I find beautiful, framed and placed in places in my house where I can see them, and change them with the seasons.

Q: What is important to you when creating your works?

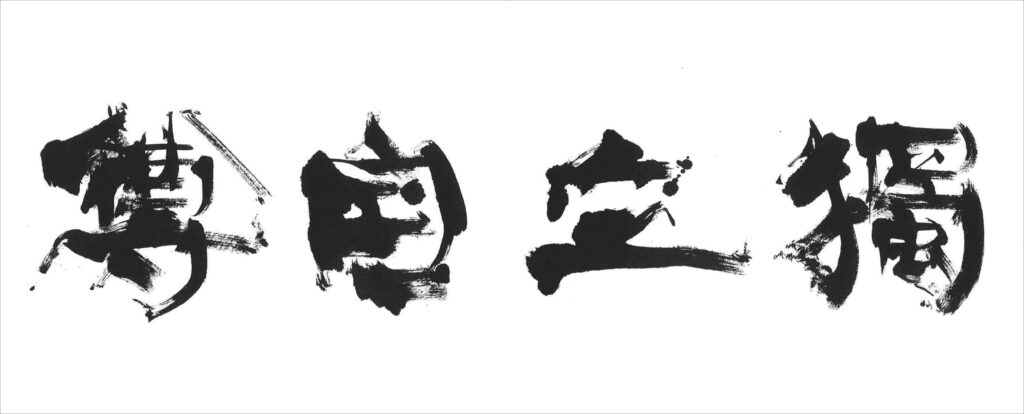

I think calligraphy should be beautiful, that’s the only thing I can say. If the calligraphy is messy and dirty, it is out of the question, but if it is just neat and tidy, that is not the case. A beautiful book usually has opposing elements in it. It is not a book with a single direction, but rather a ‘response’ of conflicting elements. I want my calligraphy to be restrained and static at first glance, but also have a dignified appearance and dynamic power.

Q: What do you think are the characteristics of your calligraphy?

My master often compliments me on my ‘good lines’. I think he means that the rest of my work is not good enough (laughs). I think I am able to produce a variety of line qualities. However, there are many parts of this that are influenced by such ‘force majeure’ as the temperature and humidity at the time. But I believe that it is precisely because things don’t go the way you want them to that calligraphy is so exciting.

Q: Do you think that calligraphy is an art that transcends the language?

I don’t know what is written, but I feel something, and I think that is what is good about calligraphy, and in that sense, it transcends language.

Q: How would you describe the attractiveness of calligraphy to people abroad?

In my experience of working abroad, I think that people overseas are more likely to understand the appeal of calligraphy without any preconceptions. They appreciate calligraphy from a formative point of view, without being caught up in the “meaning” of what is written on it. However, I would be happy if people were more aware that calligraphy is the most explored oriental art form, especially in East Asia.

Q: What do you do when you want to express an emotion through a single character?

For example, when I write the character for “anger”, I don’t try to reflect the emotion of anger in it. Also, people often think that calligraphy is written in ‘one stroke’, but it’s not like that. In my case, I write dozens, sometimes hundreds, of sheets of calligraphy for a single piece of work. When I write that many pages, with my heart devoted to each and every stroke, I am freed from my ego and feelings of how I should write, and my hand moves on its own without any thought. When I do this, I feel that I am finally able to write.

Q: How do you feel about the potential of writing?

No matter how much technology has developed, I don’t think calligraphy can be reproduced. Writing with a brush is a seemingly simple act, but can we quantify and reconstruct calligraphy, which is a delicate and complex intertwining of various elements, such as the countless nerves that move the body, breathing, sensitivity to beauty and the fluctuations of the mind, which are invisible to the eye? I believe that the evolution of technology will, on the contrary, highlight the value of calligraphy.

Q: What do you think about collaborations with different art forms such as music, butoh and

fashion?

As a calligrapher living in this era, I am positive in terms of exploring the possibilities of calligraphy in the modern age. If it is based on tradition, it is also a way of promoting the appeal of calligraphy. In the beginning, calligraphy was originally carved on ox bone, tortoise shell, bronze and stone, then it was written on bamboo and wood, and then it was written on paper. As a result of these changes in “medium”, the form of the letters has also changed to match the shape of each medium. I have collaborated with video before.

Q: How conscious are you of margins and space in your writing?

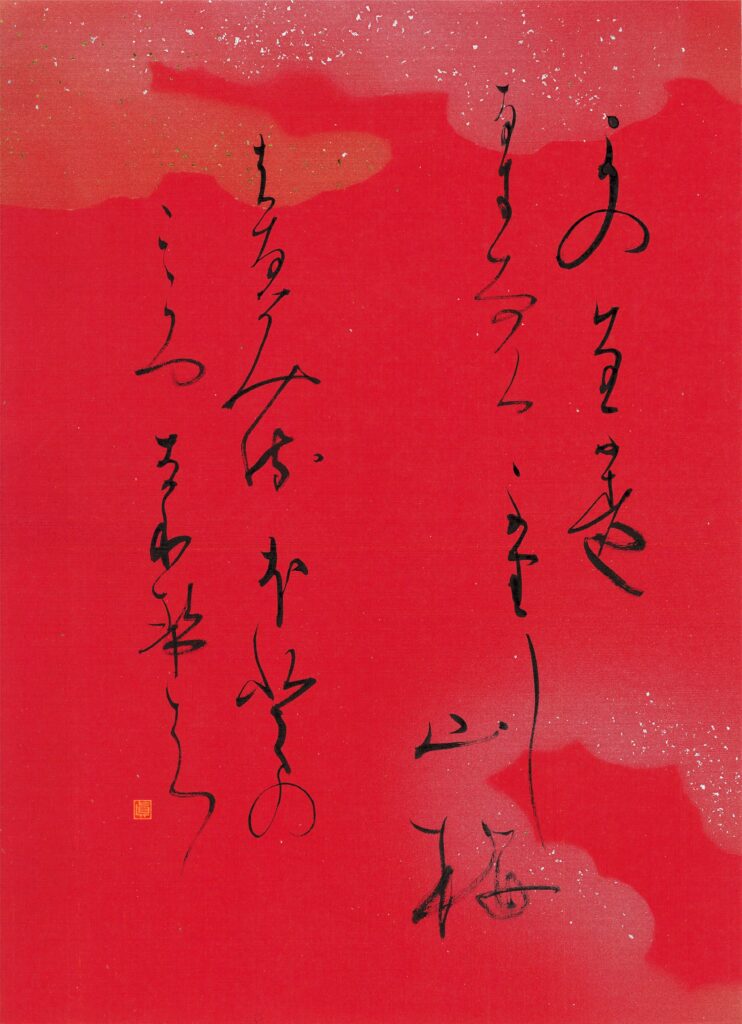

From a writer’s point of view, I sometimes compare letters to shadows and Yohaku (margins)to light, but I am equally conscious of both. People often try to fill in the Yohaku because they feel that if the Yohaku are prominent, there is not enough space, but Yohaku do not mean that there is nothing. There is a Western idea that “God is in the details”, but in Japanese terms it can be said that “Kami is in the Yohaku”, which is also what I feel while reating calligraphy. The calligraphy in which waka poems were written in the Heian period (794-1185) has a uniquely Japanese technique called “Chirashi-gaki ” (scattering writing, that is, writing unevenly), in which each line is written at an uneven height at the beginning of each line. In this style, natural landscapes are expressed by the arrangement of the characters, making the most of the blank spaces. Unlike today, where skyscrapers line the streets, the residences of aristocrats in Kyoto would have overlooked distant mountains and hills, and birds flapping their wings high in the sky, but what is expressed in the calligraphy is the landscape that people of the time perceived, with a sense of the kami behind nature.

Q: Do you have a message for the younger generation or people who are going to study

calligraphy?

I would like people to realise how narrow the scope of what is considered common sense and the scale of the present only is, that the present exists because of the past, and the future exists because of the present. I think the view of history that young people can be aware of in their daily lives is, at best, what has happened since the end of the war. But as soon as they come into contact with calligraphy, that changes to thousands of years. Beyond calligraphy and letters, there are countless predecessors and a magnificent world. There is a phrase ‘learn new things from the past’ (furuki wo tazunete, atarashiki wo shiru), which I think is an effective keyword in this day and age when many people are finding it hard to live.

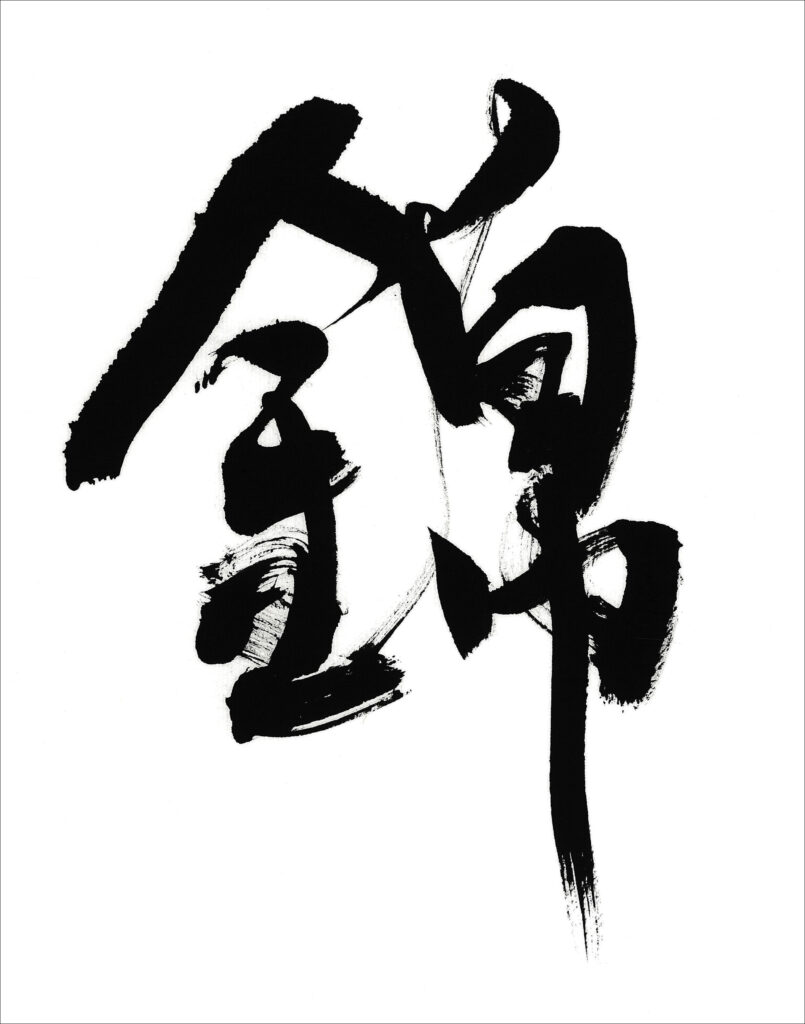

About the work ‘Nishiki’

This is one of the ‘Hana’, ‘Nishiki’, ‘Aroma’, “Yu” and ‘Kanade’, which were commissioned as the title characters for the campaign of the Shosoin exhibition. The treasures of the Shosoin Repository have been sealed and carefully preserved since the Nara period (710-794), when Empress Komyo presented the objects of Emperor Shomu’s affection to the Great Buddha at Todaiji Temple, together with Buddhist implements used at the Buddhist servise. It is in a state of preservation rarely seen anywhere else in the world, and has been handed down to the present day in its original form. As the calligraphy was to appear alongside such austere Shosoin treasures, it had to be free of any commercial nuance or excess, even if it was for an announcement. I wrote on fresh, unblemished Japanese paper, without staining it with splashes of ink or any other ‘artifice’, while respecting the texture of genuine calligraphy and the natural elegance of the work as much as possible. The title is not stamped, as I consider it to be a private work.

PROFILE

Calligrapher Mariko Kinoshita

Mariko Kinoshita explores calligraphy as a traditional culture handed down from generation to generation in East Asia. Influenced by her grandfather, she picked up a brush at the age of six and entered Daito Bunka University, which is known as a leading institution in the study of calligraphy. Studied under Seiu Takaki. She has written in five different styles of Kanji, and also works on Kanji-kana mixed calligraphy with a contemporary sensibility, based on Chinese and Japanese classics, and is in charge of the annual campaign for NHK BS’s Nippon Premium and the film Ask This of Rikyu. He has created calligraphy installations for KENPOKU ART 2016 and ETERNAL: A Thousand Seconds of Seijaku, organised by the Agency for Cultural Affairs, as well as a collection line with the clothing brand Y’s (Yohji Yamamoto). She also writes contemporary calligraphy presentations and essays on the fascination of Japanese culture.

※No unauthorized reproduction for all images of calligraphy works