The path of Shoko Kanazawa’s calligraphy began the moment she held a brush in her hand at an early age. Her pure heart and dedicated efforts have led her to dedicate her calligraphy to many famous temples, shrines and overseas stages, despite the handicap of Down’s Syndrome. Her pure heart and dedication have led her to dedicate her calligraphy to many famous temples and shrines, as well as on overseas stages. In this interview, she explains why her calligraphy moves people’s hearts, her deep bond with her mother, and the path she has taken while feeling connected to her late father. In today’s world, where competition and rationality are so important, what are the ‘truly important things’ that her way of life teaches us? What is the power of Shoko’s calligraphy? We want you to feel the answers to these questions in your heart.

Q: Why did Shoko start writing calligraphy?

Shoko has Down’s syndrome, which is a handicap, but I gave her her first brush when she was five years old. My husband and I are both calligraphy enthusiasts in the family, and perhaps we did it out of a sense of helplessness at not being able to do anything for our disabled child. However, the moment I picked up the brush, I saw that she had a wonderful way of holding it. I had a gut feeling that I would definitely improve. Looking back, 40 years ago, I was born in a time when disabled people were treated coldly and had no hope. I feel very happy to be here now, which I never thought I would be then.

Q: Has your attitude to calligraphy changed between when you first started and now?

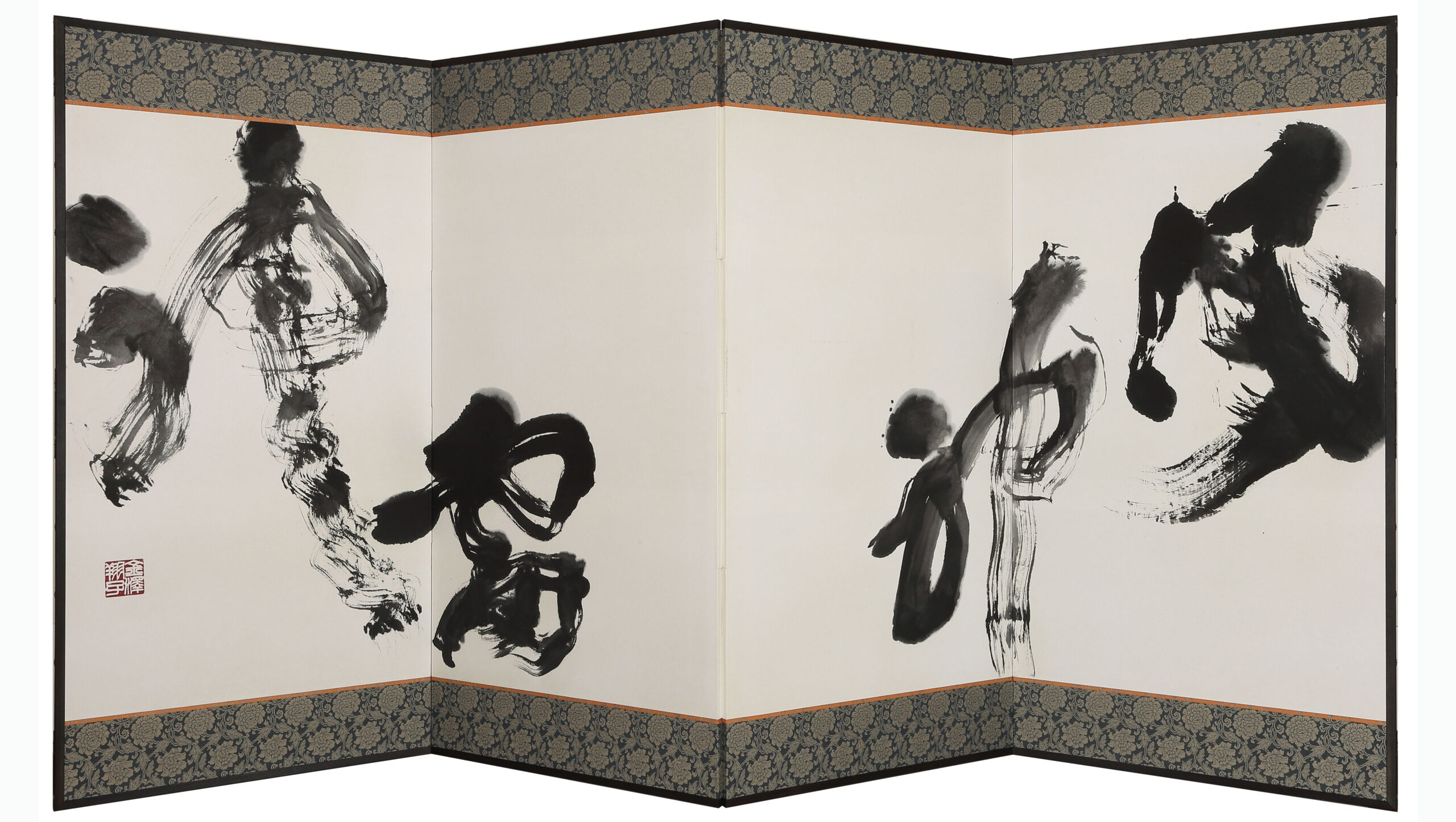

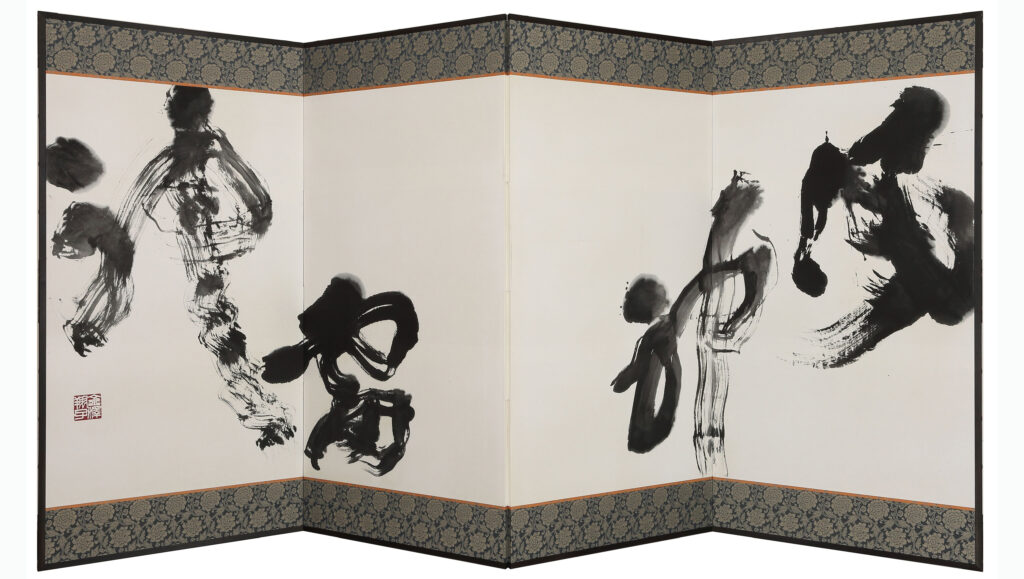

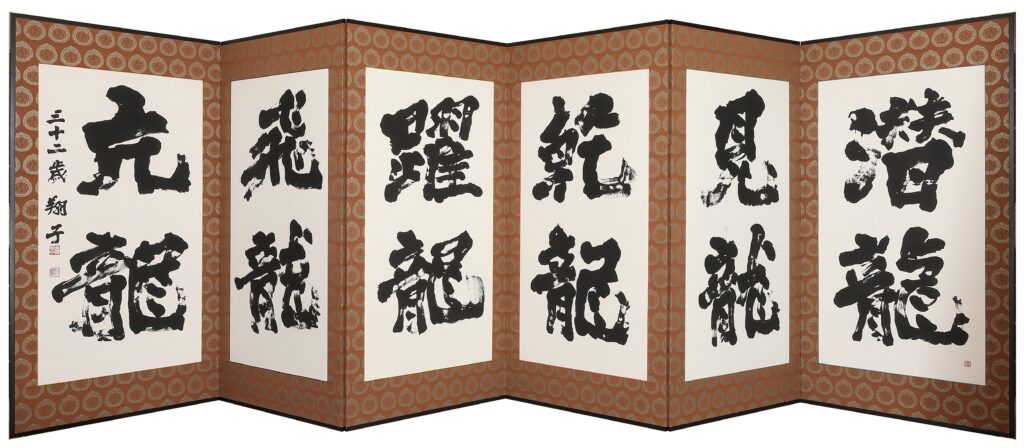

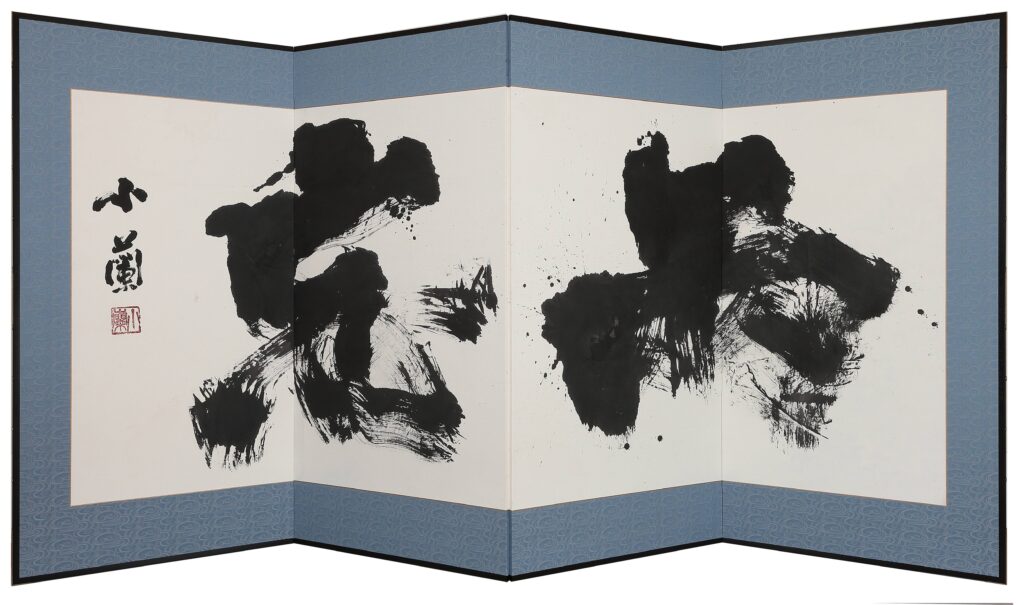

This June marks exactly 20 years since I made my debut. I have had the opportunity to dedicate my calligraphy at the head temples and main shrines of famous temples and shrines such as Horyu-ji, Todai-ji, Enryaku-ji, Yakushi-ji and Ise-jingu, and I have also had solo exhibitions in New York, the Czech Republic, Singapore and other countries around the world thanks to the support of the Japanese government. Looking back, I think that Shoko herself suffered during these 20 years after being recognised by the public as a calligrapher. After I got attention, I got a lot of work, and I had to write every night, and I was angry and cried a lot. This went on for about 10 years, and that’s how I got really good at it. At that time, writing large characters, such as on a folding screen, was rare. But when world-class temples and shrines ask me to do that, such as the 1,400th anniversary of Horyuji Temple and the 1,300th anniversary of Kasuga Taisha Shrine, I can’t say no. She just wants to please me, her mother, and that’s what she lives for, so she never said she didn’t want to, she wrote the calligraphy and has been running all these 20 years. She has never said a word about her dislike of it, and she has been writing calligraphy for 20 years now. Only Shoko can write works that are free of any such unnecessary emotions.

Q: Tell us about the process of establishing your “identity” as a calligrapher.

When people see Shoko’s calligraphy, they cry. It’s the kind of calligraphy that naturally brings tears to your eyes. I think it comes from the purity of Shoko’s desire to be a great person and not to have the same desires as other people, because she is mentally disabled and her hopes for the future are limited to tomorrow’s lunch. I don’t know anything about common sense, but I only have a pure soul and I can put 100 per cent of my energy into making people happy. If you were a normal person, you would think in the corner of your mind about whether the balance between left and right is right or wrong, or how much you can sell your work for. I think no one can really compete with me, because I write at the level of the soul, and I am moved by it. Normally, I would try to write in a balanced way so that the letters don’t stick out of the paper, but for her, it doesn’t matter. She had a hard time when she was 10 years old, and I wanted to save her, so I made her try to write the Heart Sutra for a whole year. She wrote for hours and hours all day long, and it must have been really hard work, but when she finished, Shoko would always say ‘Thank you very much’. So a foundation was naturally built during that painful year. For her, she continued to write because she wanted to please her mother, and from my point of view, it was an initiative that she made because she wanted to do something for her child, so it may be the result of the “love” that only a parent and child can share. That is why Shoko is able to write any kanji that she doesn’t even know the meaning of. It’s really strange, I feel as if I’m being guided by something.

Q: What do you mean by being guided?

Actually, Shoko’s father died when she was 14, and when she was 18 she couldn’t go to school, couldn’t find a job, and I myself became a recluse. At such a difficult time, I suddenly remembered my father’s words. He had said that when Shoko turned 20, he would hold a wonderful solo exhibition to commemorate the occasion. Some people had kept quiet about her Down’s syndrome until now, so I decided to display Shoko’s wonderful calligraphy and come out to everyone that she has a mental disability. I was excited at the time and exhibited 20 works at a famous gallery in Ginza. However, something unexpected happened. Some of the visitors who happened to be there were from temples and museums, and they were so impressed that they asked me to hold a solo exhibition at their place too. I wanted to be saved from the pain I was going through, so I held a one-off exhibition, and it turned out to be my debut as a calligrapher.

Q: Did you encounter any difficulties while continuing to write?

When you become a calligrapher, you get all sorts of orders. Especially when it comes to writing in public, there are many opportunities to write on large sheets of painted paper such as folding screens. It’s a one-shot game and you don’t know the distance. As a parent, I was worried and felt it was difficult, but I don’t think she thought so. When she wrote on a very large piece of paper at the National Athletic Meet, she held a heavy brush weighing 20 kg, but when she tried to write it, it fit perfectly and she was able to hold it up. She has a solid foundation and has not been taught anything unnecessary, so she naturally has a sense of writing with her body. Because we have been equipped with intelligence, we are only able to be educated and moulded before we know it, but Shoko has an uncommon spatial awareness that is not logical. The wonderful works of art she produces are miraculous and magical. I think it is precisely because she did not acquire a general education due to her intellectual disability that she is able to draw out the talents that are inherently human. Therefore, they can blossom in art and art, fields that cannot be described by reason. I think that such a miraculous event was really orchestrated by God.

Q: What is the most memorable event in your life as a calligrapher?

There was a mysterious event when I wrote the calligraphy in the hall in front of the Great Buddha Hall at Todaiji Temple. Of course, it was written after my father had passed away, but I was on a school excursion when I saw the Great Buddha and I think I thought it was him. I was a bit worried about the large 10-metre calligraphy, but I thought Shoko would be able to handle it, so I accepted the commission. Shoko herself was aware that she was writing in front of her father, since he had passed away. The crowd was so big that some people even climbed up the trees around me to watch the performance. With a huge crowd watching, there was an air of worry in the air that everyone might lose their concentration. Then Shoko said, ‘Thank you for your support’. It was like a word that came down from the heavens, and it made everyone feel at ease. To her, the ranting sounded like cheering. It doesn’t matter how great a person she is, she loves children and grandmothers with canes. Everyone was touched when she said, ‘Thank you for your support.’ But it didn’t stop there, before Shoko could start writing, a small animal happened to swoop in and perch at her feet. Not long afterwards, after she had firmly finished writing, Shoko said about the little animal, ‘It was my father’. So she felt her father in the public eye and wrote it up with her father. That may be a coincidence, but I can’t help but feel that her soul called to something like that.

Q: What is writing for you, Shoko?

I myself suffered for a long time with my daughter’s lifelong incurable intellectual disability. She was diagnosed with Down’s syndrome 51 days after she was born. Unfortunately, it cannot be cured, and she may never walk, but she will have to live for a long time to come. It wasn’t a society that was as kind to people with disabilities as it is today, so although I felt the most sorry for Shoko herself, I also had a hard time because I didn’t know what to do. Because I have lived in such an environment, I think the connection between parents and children is not normal. It’s not about where to put this brush to finish well or anything like that, she just writes to please me the most. For her, it’s all about living in a world where there are only me, her father and the three of us. Is there something that attracts you there?

Q: What is important to you and what do you keep in mind when you are working on a piece?

I always pray on stage for a long time before I write. During that time, I don’t care how much noise I make or if my mobile phone rings, but I ask them not to put the microphone in. It looks like I’m doing a spiritual unification, but my interpretation is that I’m purifying my heart and connecting with my father. When I’m by her side, Shoko mumbles, “Father, please let me write well”. I think that her father is still alive in her mind. For a while, when Shoko lived alone, there was a picture of her father in her room, and there was a note with her own mobile phone number on it, saying “Father, please call here if I’m not here”. Probably she does that because she believes her father will come to visit her, but Shoko believes in his presence. So I take that ritual before I write very seriously.

Q: What was the turning point in your own work?

The National Treasure Wind and Thunder Gods and Shoko’s calligraphy are exhibited side by side. It was a coincidence that a monk at Kenninji Temple put her work alongside Tawaraya Sotatsu’s The Wind and Thunder Gods because it looked so much like the latter. It became very popular, and eventually a bus tour was organised, and it has been on display there for 15 years now. I always use a lot of sumi ink when I write large works, so I write with ordinary sumi ink. I thought I had written this piece with sumi ink as well, but one day I had a chance to see it in the sun and realised that the sumi ink was different. It just so happened that I was writing with blue ink, which I had received as a sample and which does not deteriorate easily. I think it was a truly miraculous piece of calligraphy, which stands alongside national treasures, to be able to preserve it in this way through a series of fortunate events.

Q: What do you want to convey through the calligraphy?

Modern society is a difficult place to live in, even if you try to live a decent life. If you grow up in the Japanese educational process, there is a strong sense of competitive rivalry, and you sometimes feel sorry for young people. So I want them to live a pure life and not get too caught up in society. People ask me for my opinion in situations like this, but I can’t say which is the right answer because each person has their own situation. All I can say is that you should look at Shoko. Even with all these handicaps and hardships, she brings happiness to herself, and she really is ‘pure, isn’t she?’.

Q: Which do you feel is more important, calligraphy technique or sensitivity?

This may be because I am looking at Shoko’s calligraphy, but I think sensitivity is more important. Of course, in her case, she has an absolute foundation thanks to the Heart Sutra, which she memorised by repeating it over and over when she was 10 years old, but in the end, I think the difference is that she writes with sensitivity. Shoko’s calligraphy transcends the level of technique and the like; it is a calligraphy that expresses her personality as it is. I think that is why her calligraphy has the power to move the emotions of those who see it.

Q: If you were to convey the appeal of calligraphy to people overseas, how would you describe it?

I think the appeal of calligraphy is that, unlike painting, each letter has its own meaning. Originally, calligraphy developed from hieroglyphs, so the shapes of many of the characters give us their meanings. For example, the character for “mountain” is very easy to understand, but the shape of a series of mountains is directly formed into one character. If you write that character “mountain” in a strong character, you might imagine a steep mountain range, and if you write it in a gentle character, you might imagine a gentle mountain range. I feel that this is a very grand thing, but it originally started with the shape of the mountain that humans saw 6,000 years ago, and through the ages it has become the modern “mountain”. In terms of conveying this, doesn’t it mean that language is irrelevant? People abroad can sense the quality and values of calligraphy through inspiration. So no matter which country you go to, the culture of calligraphy is easily accepted, and I have been reminded that it is a wonderful art form that can be accepted worldwide.

Q: You have held exhibitions and performances all over the world.

One of the most memorable episodes was when Shoko was invited to the United Nations Headquarters in New York. It was part of an international initiative to improve the status of women and human rights, and the theme of the event was to deepen understanding of Down’s syndrome and “family support and independence”. Shoko Kanazawa took the stage and gave a speech as a representative of Japan. She spoke very magnificently, proudly wearing a kimono. When I heard her words of gratitude to her mother, I was so moved that I cried many times in the hall. Going back to that time, 30 years ago, when Shoko was informed that she had Down’s syndrome, what I had been saddened by, thinking that I was probably the saddest mother in the world, when I heard her speech, I felt that I was the happiest person in the world. It was an event that made me realise that although there are many difficulties in life, happiness will always come to us if we live.

Q: What do you think is the relationship between writing and your state of mind?

As I mentioned earlier, it is related to the ritual like mental unification that I do before writing, but I think what Shoko feels is the presence of her father and mother. I think that by feeling close to the fact that her family is watching her, or by thinking that she can hear their voices for that matter, her brain is working in the direction of pleasing them. That feeling leads to good writing. It doesn’t matter if the person has a disability or not, there will always be people around that person who look out for them and care about them. I want to please those people, and I think that if I take care of those fundamental aspects of my work, I will also feel that I want to improve and practice more.

Q: Are there any themes of expression or artworks that you would like to try in the future?

This is a far cry from writing, but Shoko is a very good dancer. She especially loves Michael Jackson and often dances to “Thriller” and “Beat It”. He is also a genius dancer, so is there something in common? For her, the first thing that was around her happened to be calligraphy, so she came to that one path for 40 years, but she has worked hard and now wants to teach her other things. At the moment, I’m renovating the floor below the calligraphy class into a café, and I’m giving Shoko a customer service job there, which is part of what I wanted to give her something different from calligraphy. If she takes a short break here, and if the desire to write on her own arises again, it might open up a new life for her, and I’m thinking of doing some interesting initiatives such as a collaboration between this café and calligraphy.

PROFILE

Calligrapher Shoko Kanazawa

Started calligraphy at the age of five under her mother Yasuko, a calligrapher. She is one of Japan’s leading internationally active calligraphers. Widely known as a calligrapher with Down’s syndrome, she has held dedications at famous shrines and temples such as Ise Jingu Shrine and Todaiji Temple, museum exhibitions, as well as solo exhibitions and performances in New York, London and other cities around the world. He donated a large work, Prayer, to the Pope of Vatican City, created the title for the NHK historical drama Taira no Kiyomori, the official art poster for the Tokyo Olympics, and wrote the inscription for His Majesty the Emperor (during his reign) In 2013, he was awarded the Medal with Dark Blue Ribbon.