Flowers and branches breathe life into a space, quietly conveying their presence within the negative space. Ikebana is not merely a form of decoration, but an extremely profound form of expression. Mika Otani, a master of ikebana, sheds new light on this world. While respecting tradition, she is a new-era artist who constantly seeks ‘beauty yet to be seen.’ Viewing ikebana as an ‘art of space’ and reimagining the space itself through her creations is truly worthy of being called contemporary art. The empty space that highlights the lines of the branches, the harmony between sparseness and density, and the aesthetic sensibility rooted in Japan’s view of nature—each of these elements embodies her philosophy. ‘Not filling the space, but creating the space.’ We want to delve into this quiet yet powerful belief.

Q: Why did you choose ikebana among the many Japanese cultures?

When I went to study abroad in the UK at the age of 19, I was often asked about Japan. I had been studying tea ceremony since I was in junior high school, and I was also a member of the koto club in university, but when I was asked, ‘What is the beauty of Japanese culture?’ I couldn’t answer properly… From that experience, I began to think, ‘I want to know more about my own country,’ and I became increasingly interested in learning a new Japanese art form. After returning to Japan, I suddenly remembered the flowers that were displayed in the tea room during my tea ceremony lessons. ‘That’s it, I’ll try ikebana,’ I thought, and with a light heart, I started attending a class near my home, which was the beginning of everything.

Q: That’s when you met Mr. Tomita Sōkō, a master of the Sōgetsu School. Is there any teaching you received from your master that you still cherish today?

There are hundreds of schools of ikebana, each with its own philosophy. Some schools place great importance on traditional styles, but the Sogetsu School is at the opposite end of the spectrum. It is very avant-garde and places great importance on the teaching of ‘arranging flowers that live in the present.’ My master was also a very creative person who created various works using plaster and other materials. He often told me, ‘Express yourself in a way that only you can’ and ‘Incorporate new ideas as art.’ Hearing that, I felt a sense of challenge. Days of trial and error, thinking, ‘What about this?’ or ‘That might be interesting too,’ have become a source of strength for me even now.

Q: In addition to presenting your own works, you have also been involved in ikebana decoration for numerous dramas and films. What do you think ‘your own style of ikebana’ is?

There are many ikebana artists exploring new expressions, but I consider myself one of the more challenging ones. New expressions are imitated and eventually become standard—that’s the fate of art. While Sogetsu-ryu’s expressions are innovative when viewed within the broader context of ikebana, some of them have already become standard within the school. That’s why I believe in continuing to challenge myself without fear, rather than staying stagnant. That’s what I consider to be my own style of ikebana.

Q: Aren’t you afraid to take on new challenges?

My desire to ‘just give it a try!’ outweighs my pride and shame. I often draw inspiration from the positive energy of the pioneers of art. Even painters and sculptors who are now considered masters were criticised when they first started out. It was by using that criticism as a springboard and sticking to their own style that they awakened true ‘newness.’ Learning about this background through museum panels or audio guides really encourages me to think, ‘I don’t need to fear a little criticism. I can challenge myself too.’

Q: Is there any recent work that you feel has opened up new horizons for you?

Last year (2024), I was invited to China and performed ikebana at a luxury resort about three hours by car from Beijing. The venue, Aranya Jinshanling Music Hall, is a famous hall known as a hub for art in China. Standing on this stage is a dream for Chinese artists. It was an honour to be able to perform in such a place, and I saw it as an opportunity to show a new form of expression, so I said, ‘I will show you how a huge ikebana arrangement is created.’ However, the response I received from the staff was, ‘That lacks entertainment value.’ They said, ‘Customers buy tickets expecting something new and interesting, so is that really new?’

Q: That was an unexpected response.

I had thought that the large-scale work and its style itself were new, so this was a revelation. How could I present a more innovative form of expression? That’s when I came up with the idea of staging the ikebana arrangement as an entertainment show. I devised a story where the Queen of the Mountains awakens the spirits and causes the flowers to bloom, and all the cast members, including myself, performed the ikebana arrangement while dancing.

Q: You also performed at a resort facility in Hangzhou, China, in April this year.

Following the great success of last year’s performance, we received an offer from the ‘Fuchun Mountain Residence’ resort in Hangzhou. The stage was a 25×25m indoor pool. We filled the pool with about 10cm of water and performed a dance while splashing the water and arranging flowers. We updated the story and are confident that we delivered an even better performance than last year. My desire to explore the possibilities of what can be done with ikebana has grown even stronger.

Q: Where do you get inspiration for new expressions?

Ikebana is said to be ‘arranged to fit the space,’ so I consider the composition after the location is decided. For example, if the arrangement is in the centre of a room, I design it so it can be seen from all directions. If it’s along a wall, I focus on how it looks from the front and sides. In my case, I start by standing in the space and mentally sketching out rough ideas like, ‘What if I arranged flowers like this?’ Following that rough sketch, I then adjust the arrangement while handling the floral materials to make it more my own. During the performance in Hangzhou, China, I spent a lot of time on this adjustment process. Although I had been informed beforehand that the stage would be a ‘25×25m pool,’ when I actually stood there, the space was far more vast than I had imagined. Determined to create a piece that could match the scale of this space, I continued to make adjustments, and the piece gradually grew larger and larger. In the end, it became a work that resembled three large mountains towering over the space, rather than traditional ikebana.

Q: Besides locations, what other things inspire you?

I sometimes get inspiration from architecture. When I see an interesting building, I think, ‘Could I express that structure through ikebana?’ I also get ideas from makeup. Makeup has limited expressive possibilities, so you have to draw lines and layer colours within a limited space. I am fascinated by the accumulation of such ingenuity. I thought it might be interesting to incorporate artistic makeup into my performances, so I tried out various makeup styles at a Shu Uemura store. Seeing how the impression of the face changed dramatically with just one line made my heart leap.

Q: Architecture and makeup have something in common with ikebana. When arranging flowers, how do you think about the use of ‘white space’?

In ikebana, there is the concept of valuing lines. To make the viewer feel that ‘the line of this branch is beautiful,’ there needs to be negative space beneath the branch. For example, if a branch extends long, the space beneath that branch should be left as negative space. If this space is filled with something, the beauty of the line is diminished.

Q: Is it because of the negative space that the beauty of the line stands out?

Exactly. Another important point is to consider the balance between ‘sparseness’ and ‘density.’ While there are areas with ample negative space to create ‘sparseness,’ there are also areas where flowers are densely arranged to create ‘density.’ How to balance sparseness and density becomes particularly challenging in large-scale works.

Q: You have extensive experience working overseas. What do you think is the essence of ‘Japanese aesthetic sensibility’ that you wish to convey to people around the world?

In Western flower arrangement, flowers are the main focus, with leaves and branches used as accents. In contrast, Japanese ikebana is based on the idea of loving nature as a whole. This is true of all schools. The aesthetic sense that flowers, leaves, and branches are all precious and irreplaceable is something I would like to convey to people overseas.

Q: Have you had any difficult experiences overseas where the Japanese sense of ikebana was not understood?

Western flower arrangements are suitable for catering, but ikebana cannot be transported. Since ikebana is created after confirming the size of the space and the atmosphere of the venue, it is often difficult to convey that ‘it cannot be created in other places’ and ‘once it is created, it cannot be moved.’

Q: Flower arrangements give the impression of densely decorating vases or baskets with flowers. Isn’t the sense of space also different between Japan and overseas?

Yes. The fundamental concept of flower arrangement is to ‘fill the space.’ If there is one square metre of space, it is filled with flowers. When I go overseas, I am often asked, ‘How much does Mika’s work cost per square metre?’ However, my work sometimes has one side filled with flowers and the other side with just one branch, so I am at a loss when asked about the price per square metre. So, when asked that question, I always respond, ‘It’s not about filling the space; it’s about creating the space.’

Q: What do you do when that concept doesn’t come across?

Overseas, there are no preconceived notions about ikebana, so when I show my work, people often understand it immediately. They welcome me with the understanding that ikebana is Japanese flower art, so they usually entrust me with creating their art. In that sense, I feel more relaxed and free to work overseas.

Q: Is it more difficult to work in Japan?

In Japan, there is a strong image that ‘ikebana is the world of wabi-sabi,’ and when people hear ‘ikebana,’ most of them imagine works that are displayed in the alcove. Of course, there are traditional works like that, but what I create is a new style of flowers that incorporates the atmosphere of the modern era. In order to increase the number of people interested in ikebana, I want to spread the recognition that ‘ikebana is art.’ My involvement in films, dramas, and stage productions is also to help more people learn about ikebana.

Q: In the 2018 drama ‘Takane no Hana’ (Nippon Television), you created 174 works, didn’t you? Recently, you have also been involved in many popular works, such as ‘1122 Iifufu’ (Amazon Prime Video) and ‘Jimen-shi-tachi’ (Netflix).

In the past, staff members from films and dramas would often ask me, ‘Is this ikebana?’ with a puzzled expression. Recently, people have come to understand ‘Mika Ohtani’s ikebana,’ and I am grateful that I am given more opportunities to take on challenging themes. When I am given themes that I would never have thought of myself, such as ‘Please create a suspicious-looking flower’ or ‘Please express murder,’ I get excited and feel like I am challenging myself to see how much I can express within the constraints.

Q: Besides working on films, dramas, and stage productions, do you do anything to promote ikebana?

Since 2023, I’ve been doing installations at the Kanemori Red Brick Warehouse in Hakodate, Hokkaido. It’s an event where people who live in Hakodate, visitors to Hakodate, and other guests can arrange flowers that were grown in Hakodate. No matter how much I try to explain the joy of arranging flowers, it’s frustrating when it doesn’t really get across. Therefore, I believe the best way to convey this is through hands-on experience, which is why I regularly hold such events. In 2023, 1,000 guests arranged 1,000 alstroemeria flowers to create a single piece. It was delightful to see people of all ages participating with such enthusiasm. This year, we plan to arrange 700 sunflowers.

Q: That is a wonderful initiative. Are there any habits you prioritise in your daily life as you continue your creative work?

‘Not treating flowers carelessly.’ Flowers used for photography or interviews are brought home and rearranged simply. If flowers are allowed to wilt or are treated carelessly, I feel they won’t be there to support me when I need them. It’s like my own superstition. Before major performances or projects, I quietly greet the flowers I’ll be using, saying, ‘Please take care of me today.’

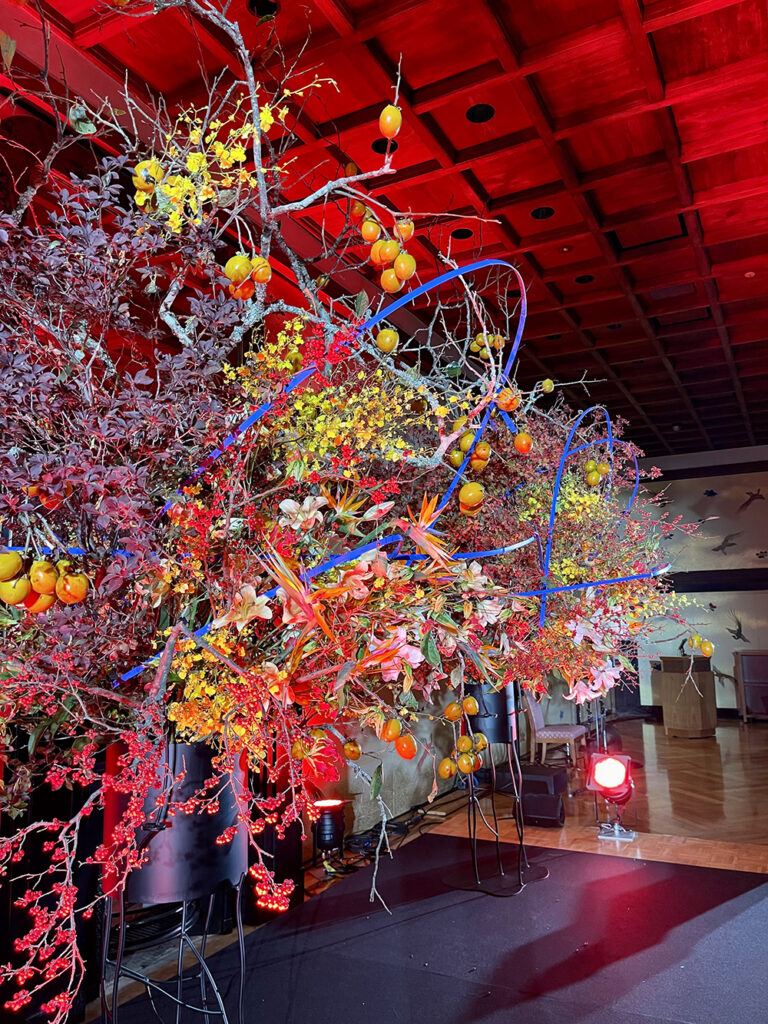

Q: About the featured work

Work title: ‘Flowers Smiling.’ Earth Art Festival Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale Exhibition Work Photography Kozo Sekiya. From the powerful earth, a ‘flower of hope’ is born anew and blooms. A flower that blooms without withering, facing the sun of hope. Branches that grow, drawing dreams that never cease from the earth. Expressing ikebana as art.

PROFILE

Ikebana Artist / Sogetsu School First-Class Master and Council Member Mika Otani

Entered the Sogetsu School in 1990. Studied under the late Tomita Sōkō, a direct disciple of the first Sōfū-ryū headmaster. Founder and director of the ikebana studio ‘Atelier Sōkō.’ Has been involved in numerous film, drama, and stage decorations, and is active not only domestically but also internationally. Her innovative and artistic expressions captivate many viewers and represent the true essence of new Japanese culture.