Mika Toba, a dyeing artist pursuing unique expression within the world of katazome—a traditional Japanese technique of which Japan is proud. Carrying within her the aesthetic sensibility cultivated in Kyoto, she sublimates the fervour and energy encountered in Vietnam into her work, expanding her activities globally. The works Toba creates are at times as delicate as light rippling across water, at others as powerful as the fervour enveloping a city. Their vivid colours and overwhelming scale draw the viewer into a singular, unique world. The origins of her art, pivotal events, and the wish for peace embedded within her work—let us listen to the trajectory of her creative journey, rooted in tradition yet perpetually seeking new forms of expression.

Q: First, could you tell us about your earliest experiences with art?

My earliest recollection of art dates back to around the age of three. My parents had an interest in Buddhist art and often took me to temples in Kyoto and Nara. Among these, the Buddhist statues in Nara left a particularly strong impression. I still treasure photographs taken at Yakushiji Temple before its reconstruction. Reflecting on this, Buddhist art may well be the origin of my artistic journey.

Q: What prompted you to aspire to become a dyeing artist?

From childhood, I drew pictures constantly, without anyone telling me to. Perhaps I was particularly good at it. After graduating from high school, I enrolled in the Crafts Department at Kyoto City University of Arts. The Crafts Department offered various courses, including lacquer, ceramics, and dyeing and weaving. Among these, I felt dyeing held the most promise for the future, so I decided to pursue this path.

Q: Among the many dyeing techniques, why did you choose stencil dyeing?

Japanese dyeing possesses unparalleled advanced techniques and history. Stencil dyeing, in particular, developed as a uniquely Japanese technique. Following the cessation of the missions to Tang China, wax ceased to be imported from abroad. Consequently, a new resist dyeing method emerged using rice bran. Shōsōin treasures include artefacts utilising stencil patterns. This katazome adorned samurai attire, such as Yoshitsune’s arm guards, and from the Edo period onwards, it was widely employed for kimono. I became deeply fascinated by this uniquely Japanese dyeing technique with such a long history.

Q: What do you find particularly interesting about katazome?

Each step in the katazome process is independent. The final appearance of the piece remains unknown until every stage is completed. Only when the paste is finally washed off in the final rinse does one encounter the completed piece. This sense of “having no choice but to press forward” is, I believe, a major charm of katazome. There are eighteen steps in total, and you cannot see ahead until you proceed to the next stage. Therefore, you take your time, enjoying each individual process as you build it up. Furthermore, once the stencil is carved, you cannot alter its shape afterwards. It truly is a one-shot deal. This sense of decisiveness is another unique and compelling aspect of stencil dyeing.

Q: Many of your pieces feature intricate patterns. Does carving the stencils take a long time?

It depends on the design, but it can sometimes take several months. It feels akin to apprenticeship or copying sutras. When carving stencils, I often realise that I rarely carve exactly as the sketch dictates. It’s more like drawing with a knife, using the sketch as a reference. I make adjustments on the spot, thinking things like, “This area needs a bit more vigour”.

Q: Regarding the resist dyeing process unique to katazome, involving a special paste, could you share any anecdotes about trial and error concerning the paste mixture, application technique, or drying methods?

Applying the paste actually demands highly skilled technique. No matter how meticulously the stencil is carved, if the paste application isn’t done well, the beauty of the finished piece is compromised. For instance, if the paste seeps inside the stencil lines, the sharpness of the lines is lost. If the paste thickness isn’t uniform, it dries unevenly. It mustn’t be too thick, nor too thin or it cracks. Therefore, I meticulously adjust the paste’s hardness and viscosity according to the desired pattern. I feel this stage is the most delicate and technically demanding part of stencil dyeing.

Q: How do you achieve such depth of colour and expression of light, utilising techniques like dye selection, layered dyeing, and gradation?

We use chemical dyes, purchasing them in powder form. We have around 60 colours, primarily primary hues. Even the tiniest amount, barely a pinch, can completely alter the colour. This is precisely why the colour variations are infinite, and reproducing the same colour is extremely difficult. This “infinite palette” holds immense appeal for me. By fixing the dye with steam, it bonds with the silk, creating a deep, luminous sheen that seems to radiate light. The dye penetrates deep into the fibre to develop its colour, so unlike paint sitting on the surface, the hues emerge as if seeping from within. For instance, layering red and blue simultaneously brings out the underlying colour beneath. These serendipitous overlaps and effects feel almost magical, sometimes yielding expressions I hadn’t anticipated.

Q: I see, it’s a profoundly deep world. Are there particular points you focus on when selecting tools or materials?

No matter how much effort and skill you invest in dyeing, ultimately it remains “fabric”. Consequently, the quality of the cloth itself profoundly influences the work. For instance, whether it has a sheen or small knots on the surface, the characteristics of the fabric completely alter the expression of the dye. What I ultimately settled on is Hakusan Tsumugi, woven in the mountain village of Shiramine in Ishikawa Prefecture. It’s a precious fabric now woven only in this area. While typically used for kimono, I have it specially woven into wide bolts for my use.

Q: Could you share any pre-production routines?

My day begins around 5am, before sunrise. I enter the studio next to my home, where my routine involves burning incense or brewing tea before commencing work. I often use blue hues, which may be connected to the morning light. There’s that fleeting moment just before dawn when the sky turns a deep, intense blue, isn’t there? I feel such shifts in colour are unconsciously reflected in my work. Even when staying abroad, I make a point of rising early to sharpen my creative senses. The atmosphere of the city slowly coming to life in the morning, the signs of people’s daily routines, the sounds that reach me – these can also influence my work.

Q: In your career so far, has there been a particular piece or event you feel marked a turning point?

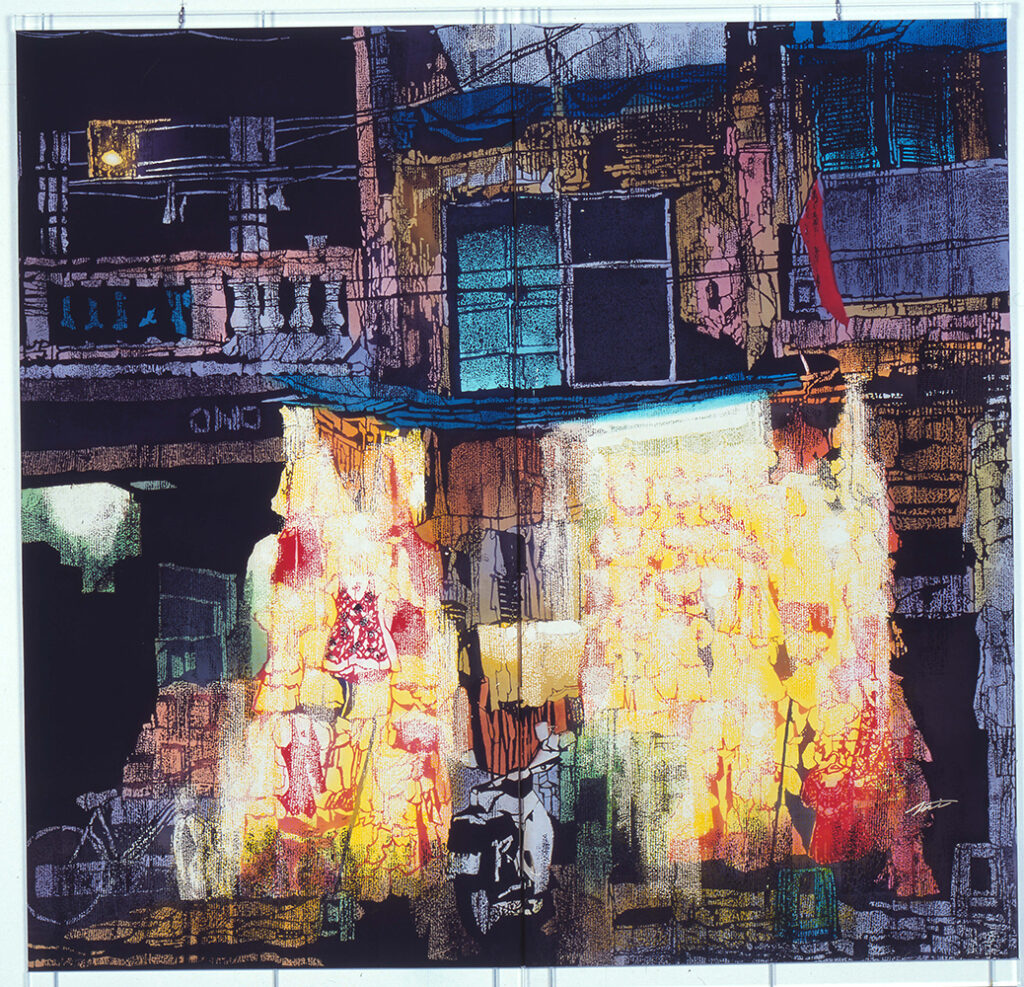

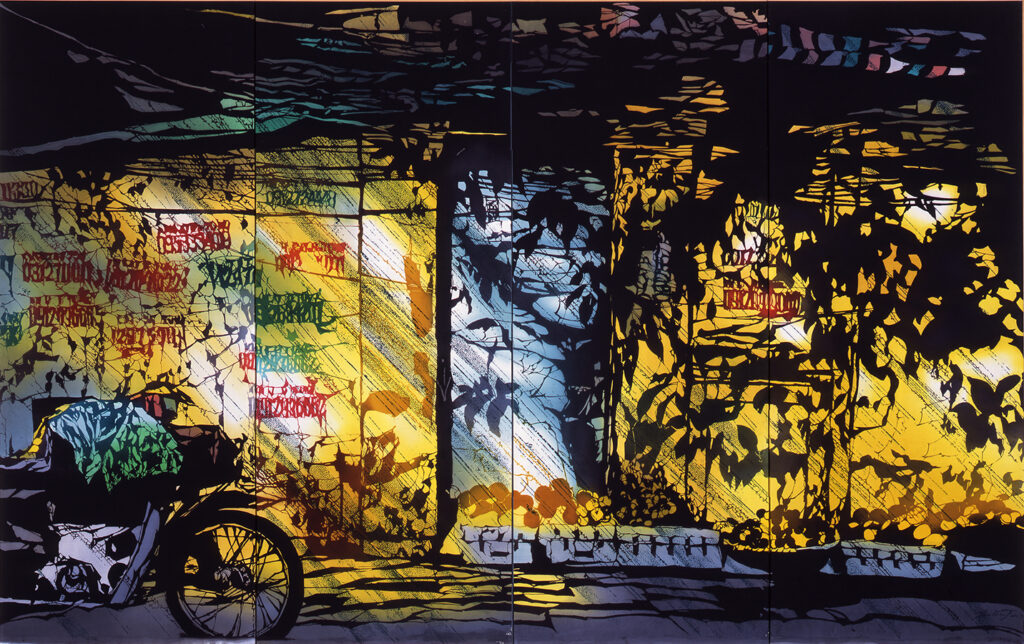

Kyoto’s dyeing tradition is a world that reveres heritage. Following that example, I too have depicted what are considered “beautiful things” – like flowers, birds, wind and moonlight – ever since my student days. Yet gradually, I began to wonder, “Could it be that what I truly wish to express lies elsewhere?” It was around that time I happened to visit Vietnam. This was in 1994, when the first direct flight from Japan had just commenced. Upon actually setting foot there, I found everything I was seeking at that time was present. The remnants of a thousand years of Chinese rule and the French colonial era, the rich natural environment. But what struck me most profoundly was the fervour and energy, as if the entire nation were charging headlong in one direction towards economic development. I was deeply moved by that vitality, so utterly different from Japan’s.

Q: Could you share a memorable incident from that time?

The day I visited Vietnam was National Day. Flags fluttered everywhere throughout the city, and it was filled with tremendous energy. Combined with the heat, I recall the city being enveloped in such intense warmth that it was impossible to tell whether it stemmed from energy or humidity. At that moment, I felt strongly that ‘if I could incorporate this country’s energy into my dyeing work, it would surely produce fascinating pieces.’ As I was exploring new forms of expression at the time, I think I was deeply drawn to the changing face of the city. Rather than places that ‘never change no matter when you visit,’ it was the energy of that fleeting moment – the sense that ‘it might be gone the next time I come’ – that truly stirred my creative drive.

Q: So you were influenced by Vietnam’s landscapes and culture as a whole?

Vietnam at that time, while a socialist country, flexibly embraced capitalist ideas too. Its tolerant attitude of ‘accepting anything good’ made a strong impression. That flexibility resonated with my own feelings of creative stagnation. I didn’t set out to change anything, but as I immersed myself in that atmosphere, the direction of my work naturally shifted. My focus moved from the “beauty of negative space” I had previously cherished towards meticulously depicting Vietnam’s “vanishing landscapes”. I pondered how to express the invisible energy and fervour, arriving at a new technique: using moulds carved with minute, pointillist-like patterns and incorporating them as texture. However, no matter how much I challenged myself with new expressions, I never abandoned the fundamental technique of stencil dyeing: “carving the stencil and applying the paste”. I felt that Japan’s traditional techniques were my origin, the method that felt most natural to me.

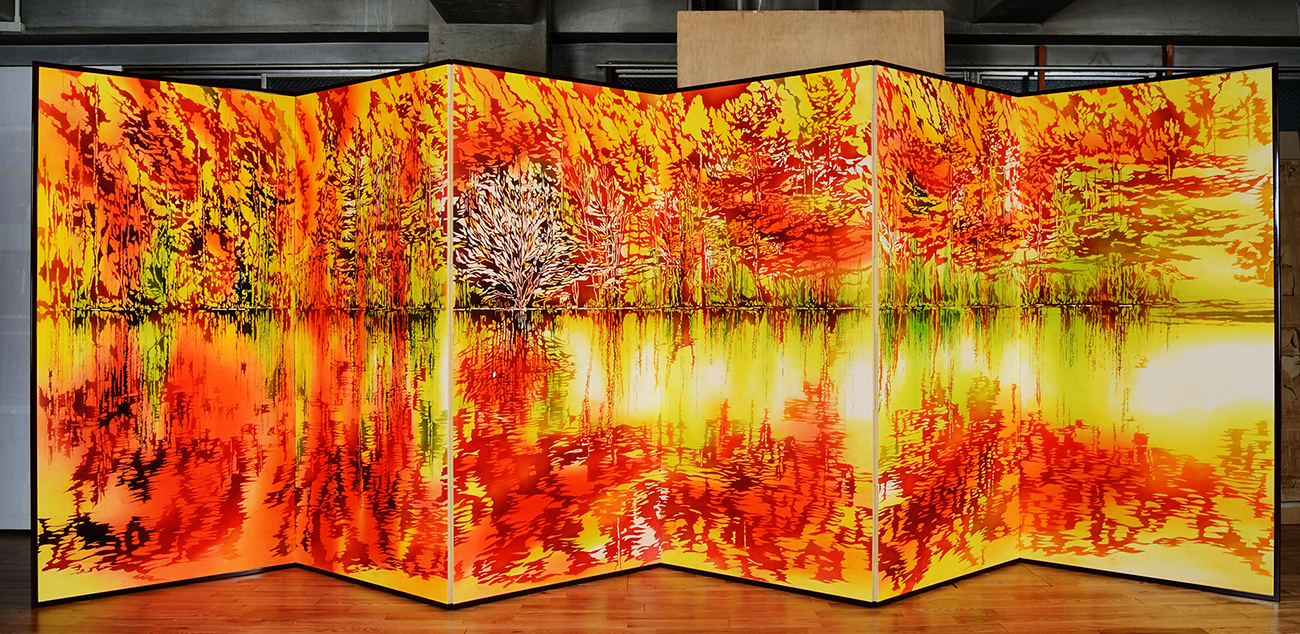

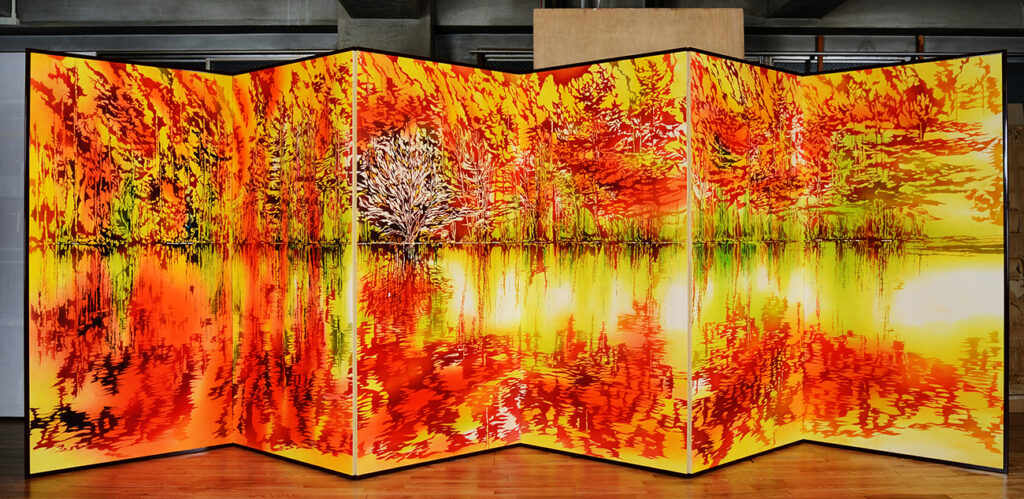

Q: Your works often give the impression of being large in scale. Did the scale of your pieces also change after visiting Vietnam?

I believe that is precisely the case. When I first set foot in Vietnam, I felt a powerful urge to absorb the landscape with my entire being. I wanted to channel that sensation directly into my work, which naturally led me towards larger-scale pieces. Even now, I consciously aim for that sense of scale in my creations, hoping viewers might share, even slightly, the atmosphere and light I personally experienced there.

Q: How do you perceive the role of paintings within a space?

I believe the “beauty of utility” – that is, objects combining practicality and beauty – is crucial. Fusuma paintings and folding screens are emblematic of this. The appeal of folding screens lies in their ability to be folded and moved; simply placing one can instantly transform a space. Indeed, during an exhibition in Vietnam, merely setting up screens in a large venue instantly transformed it into an exhibition space. While wall space is typically required for displaying paintings, folding screens can create their own exhibition space even in locations with only windows.

Q: Do you believe it is possible for a painting to encapsulate the passage of time?

During my visit to Vietnam, I was struck by how its streetscapes blend influences from over a thousand years of Chinese domination and French colonial rule with the vibrant scenes of post-independence life. Scenes from various eras are condensed there. I thought that if I were to depict people within that space, the viewer’s perspective might be drawn to the era or background of those figures, making it harder to sense the “layers of time” flowing through the entire work. By deliberately avoiding figures, I hope each viewer will interpret the flow of time through their own sensibilities.

Q: When fusing tradition with modernity, is there anything you consciously focus on?

I don’t consciously aim for modernity. I simply paint honestly what I wish to express now, what lies before me. However, I hold Japan’s cultivated traditional techniques in very high regard. While many materials exist that allow for easier painting, I deliberately adhere to traditional techniques, wishing to explore their full potential. According to research papers by scholars of the Shōsōin treasures, most techniques we can employ today were already perfected during the Nara period. It is sometimes said that techniques have already been exhausted, having passed maturity and even entered a state of degeneration. I find it truly astonishing that such magnificent works were created in an era when nothing existed. Precisely for this reason, I believe there is significance in inheriting and passing on these mature techniques as a painter living in the present day. I also convey this sentiment to my students when teaching at university.

Q: As a contemporary dyeing artist, how do you perceive your own raison d’être?

Working overseas, I am often reminded anew of how Japanese dyeing works are valued and how significant this technique truly is. A single piece is born through the support of many artisans: those who dye the cloth, those who prepare the paste, and the mounters. That is precisely why, when holding exhibitions, I believe it is vital to properly introduce these individuals, to encourage one another so that the skills are not lost, and to preserve the tradition together.

Q: What is the essence of dye painting that you wish to pass on to younger generations?

This may sound somewhat philosophical, but I believe the essence of dye painting can be likened to “a human life”. At birth, a person is wrapped in pure white cloth. As they grow, they don various fabrics of different colours and patterns, walking through life. Finally, they are once again wrapped in white cloth at life’s end. The dyeing technique, I feel, precisely expresses in colour the experiences and events encountered at each stage of life, from birth to death. Walking through life’s milestones, adorned in various colours. This journey resonates deeply with dye painting.

Q: What questions do you wish to pose to society and people through your work?

I devote myself to creating works believing in a future where pieces donated to temples might endure for centuries. We live in an era marked by global conflict. I hope that people living hundreds or thousands of years hence may view my work in peaceful surroundings. Through my art, I wish to convey this aspiration for peace.

Q: Regarding the featured works.

The fusuma paintings “Calm” (featured on the cover page) and “Setting Sail” (featured on the preceding page), dedicated to Kennin-ji Temple for the 800th anniversary of the founding monk Eisai Zenji’s passing, depict the way things in this world meet, flow, and return, designed within the space of a Zen temple. ‘Calm’ depicts a world of stillness, dominated by a silence like an ink painting before dawn breaks. “Setting Sail” portrays a world bathed in light, where ripples spread across the water’s surface as a boat departs at dawn, enveloped in crisp, clear air. As one approaches the mountain of spirits, the chanting of monks echoes, expressing a world where an eternal realm of calm awaits.

PROFILE

Dyeing Artist/Mika

TobaGraduated from Kyoto City University of Arts Graduate School. Pioneered a new realm of dyeing painting by mastering ‘katazome’ (stencil dyeing), a uniquely Japanese dyeing technique. Since her first visit to Vietnam in 1994, she has created a series of large-scale works depicting scenes of Vietnam disappearing amidst economic development, for which she was awarded the ‘Cultural Merit Award’ by the Vietnamese government. Domestically, she has received 19 awards including the Urban Culture Encouragement Award and the Kyoto City New Artist Award. She was also honoured with the Minister for Foreign Affairs Commendation for her cultural activities contributing to the enhancement of Japan-Vietnam friendship.