Painter Masatsugu Ito pursues the spatial art of fusuma paintings, fusing the traditions of Japanese painting with contemporary sensibilities. Raised with Japanese painting from childhood, he once ventured into contemporary art expression before being drawn back by the profound depths of Japanese painting. Ito’s fusuma paintings naturally integrate into living spaces, enveloping viewers in a rich, contemplative atmosphere. Underpinning his work is an unwavering conviction: ‘Art does not belong solely within museum walls.’ We explore the trajectory of his creative journey and profound philosophy, which honours tradition while seeking new possibilities for beauty.

Q: Could you tell us what led you into the world of art?

My father painted Japanese-style paintings, so I naturally entered the world of art. From childhood, drawing pictures and doing crafts was simply the norm. However, I didn’t actually handle Japanese painting materials until I entered university. Of course, I had seen my father boiling animal glue at home, but he never let me touch it.

Q: Although you specialised in Japanese painting at university, after graduating from graduate school, you moved towards contemporary art, I understand.

My father’s influence led me to specialise in Japanese painting, but as I studied at university, I began to feel uneasy about a somewhat closed atmosphere. I started wondering, ‘Is Japanese painting really the right path for me?’ and gradually became drawn to contemporary art expressions. After graduating, I focused on creating works like installations and objets d’art.

Q: Why did you return to Japanese painting?

The catalyst was a phone call from a university classmate. He invited me: ‘There’s an exhibition called “Tama ni 3+1 Ten” at Matsuzakaya in Ginza. Fancy joining us?’ At that point, I’d already distanced myself from Japanese painting, and department store exhibitions of Japanese art were strongly associated with traditional artists showing their work. So, intending to politely decline, I replied, ‘If they’ll accept three-dimensional works, I could submit something.’ Normally, that would have been a rejection, right? But he passed my offer on exactly as it was to Mr Hōji Itō, who was organising the exhibition. To my surprise, Mr Itō responded positively, saying, ‘You’re submitting a sculpture? Well, we’ll have to think about where to display it,’ without any hint of rejection. Hearing that, I was struck. Professor Ito was a major figure in the world of Japanese painting, someone at the heart of the “Inten” exhibition. That professor was seriously engaging with my three-dimensional work. At that moment, I realised it wasn’t the world of Japanese painting that was closed-minded; it was myself who had decided, rather arrogantly, that contemporary art was cooler.

Q: Was that the catalyst for your decision to return to Japanese painting?

The exhibition was set to run for three years with the same members, so I thought I’d use this opportunity to seriously engage with Japanese painting from my own perspective. To put it grandly, I wanted to “draw a line under it”. Even if I were to quit Japanese painting, I felt I should properly commit to it first. After dedicating three years to it, I found it unexpectedly fascinating. I came to think, ‘Ah, this is what I should be doing.’

Q: What kind of works did you exhibit?

The first year, I painted rocks. The following year, cacti. And for the final year, thinking “cherry blossoms are quintessential Japanese painting”, I challenged myself with the classic theme. Perhaps it was precisely by painting such a familiar subject for Japanese people that I was able to delve into the charm inherent in traditional Japanese painting.

Q: What do you consider to be the unique characteristics of Japanese painting?

Japanese painting features “kotsugaki” – the outline drawn in ink before applying colour. This differs from the Western practice of erasing lines; capturing form through linework is a defining characteristic. I feel this art of line, common not just in Japan but across China and the East, is deeply ingrained in our DNA. Lately, I’ve found myself pondering: who is more Japanese – those who paint in the Japanese style, or those who create manga and anime? Perhaps manga and anime are actually more adept at reimagining and presenting pre-Edo painting culture for the modern era. Lines are crucial in manga, aren’t they? Even without brushes, pen strokes resemble brushwork. The techniques for unfolding narratives also share common ground with Japanese picture scrolls. Sometimes I think manga artists and animators might be far more Japanese than contemporary Japanese painters.

Q: That’s an interesting perspective. When did you start painting fusuma-e?

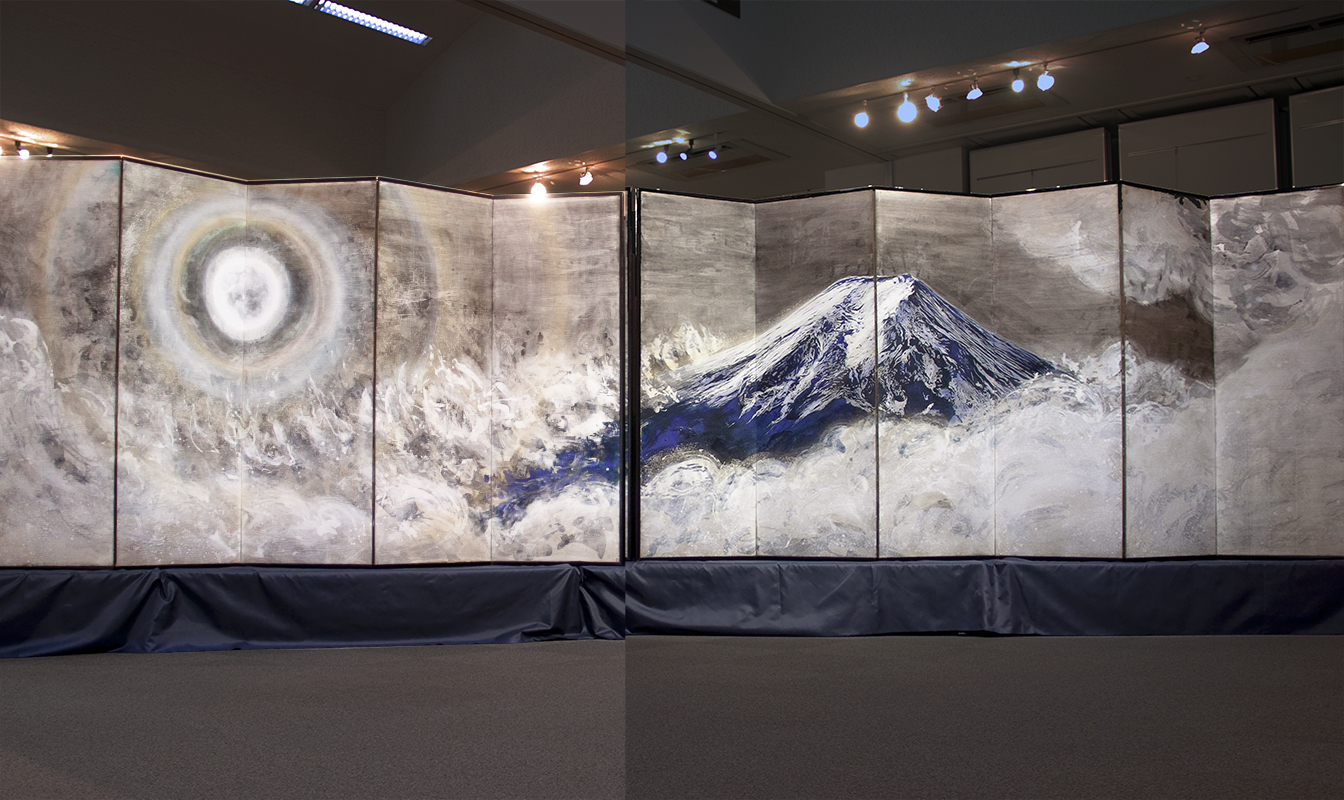

I rather simplistically thought, ‘When it comes to Japanese painting, fusuma-e must be it.’ The thing is, I’d always felt a certain discomfort with the “tableau” style, where works are framed and displayed. That format originated in galleries, after all. In contrast, the expression of fusuma-e, which expands across the entire space, felt incredibly natural to me.

Q: What can fusuma-e uniquely achieve, or what worldview can it present?

The foremost aspect is undoubtedly “space”. Fusuma-e exist as if enveloping the entire space; rather than confronting the painting, the viewer comes to feel the atmosphere of the place itself. The idea is not for the painting to stand alone, but for the viewer to experience the whole space as a single world. Traditionally, Japanese art has a culture of naturally integrating into daily life, like the “tokonoma art” displayed in alcoves. For instance, bonsai, hanging scrolls, and stones would come together to create a unified worldview. Personally, through fusuma paintings, I want to explore ways to incorporate art into living spaces and enjoy it there. Of course, museums are important, but I believe there are things that simply cannot be fully conveyed within them.

Q: Could you also tell us about your creative process? How do you select your subjects?

When sketching, I try not to think, “This will be my next piece”. It might sound a bit dramatic, but it’s closer to a feeling of being “called”. If I simply keep myself prepared, subjects seem to naturally come to me – from the heavens, or perhaps through acquaintances. I often find myself painting subjects that come to me in this way, simply surrendering to them.

Q: Regarding being “called” by a subject, could you share a specific anecdote?

Shortly before the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, in February, I painted a work titled “Scattering Flowers”. It was a subject I’d never tackled before, depicting withered flowers quietly scattering. I completed the painting within February and exhibited it in mid-March. Then, in April, when I visited the venue, the painting was displayed quietly in a dimly lit room, affected by the planned power cuts following the disaster. The moment I saw that scene, I found myself utterly unable to comprehend why I had painted such a picture… Yet simultaneously, I had this strange sensation, as if something somewhere had urged me to paint it. Since then, I have continued to paint “Scattering Flowers” every year.

Q: It’s curious why you felt compelled to paint a Scattering Petals Picture at that particular moment.

Yes, it is. It feels less like I want to paint something, and more like I’m giving form, through my own body, to something society is seeking, something yearning to be released into the world. Capturing that ‘something’ that wants to be expressed and turning it into a painting. That’s the ideal state of mind for painting, I think.

Q: Do you have a routine when creating?

It’s not a routine, but during creation, sleeping beside the painting is paramount. Ideally, the painting exists within my daily life – waking suddenly to find it there. Even during meals, glancing at the painting while thinking of other things, something might suddenly reveal itself. That time is incredibly important.

Q: How long does it take to complete a single fusuma painting?

For larger works, including the research period, it generally takes about a year. Once I actually start painting, it takes around four to five months. For smaller paintings, say a 50-number size, I finish them in about two weeks to a month.

Q: Apart from your artistic practice, do you have any lifelong pursuits?

I travel to various places in search of motifs I wish to paint. There was a period when I visited famous trees like cherry, pine, and ginkgo. I haven’t been able to go much lately, but I hope to find time to resume those journeys.

Q: Does encountering nature’s diverse forms during your research prompt you to consider environmental issues?

Recently, I’ve been thinking particularly about natural materials. Most materials used in Japanese painting return to nature when buried in the earth. Acrylic, which I sometimes use, releases gases when burned. This has made me appreciate the importance of natural materials anew. Recently, for a project depicting Hiroshima’s atomic bomb survivor trees, I used paper from the non-profit organisation “Circular Cotton Factory”, which makes washi paper from recycled hotel sheets. It made me realise art can also serve as a beacon for such initiatives. We are no longer in an era of mass consumption and mass disposal; I believe art, too, should be circular.

Q: Mr Ito, you have collaborated with various artists over the years. Among these, is there any collaboration that particularly stands out in your memory?

The collaboration with Noh theatre was truly fascinating. Typically, the backdrop of a Noh stage features a “mirror panel” (kagamiita) painted with pine trees. We placed a fusuma screen painting of Mount Fuji in front of this. While Noh performers might consider this a breach of etiquette, we created a single work together with the Noh actors and traditional Japanese musicians. Noh theatres typically illuminate the entire stage brightly, but I felt that approach was wrong. In the past, performances were sometimes staged using only torchlight. So, I deliberately plunged the stage into near-total darkness. Noh masks have only tiny holes, about 5 millimetres wide, so the performers said, “We can’t walk in such darkness.” Yet they moved by instinct. Deliberately creating a state where, in the darkness, no one could tell what anyone was doing – this attempt to recapture Noh’s original atmosphere offered a different kind of fascination from painting.

Q: I see. You’re also involved in various activities in your home prefecture of Ehime.

At the Kamikuroiwa Rock-Shelter Site in Ehime, around 20 of Japan’s oldest paintings, dating back approximately 14,500 years, have been discovered. These are Venus figures of women, carved into hard stone. Childbirth in those days was life-threatening, so it’s thought these might have been kept as amulets for safe delivery. Wanting more people to learn about this precious site, last year I held an event in an old Ehime house where participants painted on shoji screens. We painted Jōmon-era women and animals onto shoji screens, then illuminated them from behind with paper lanterns. It was an attempt to revive ancient paintings within a modern space. I constantly think about how art can serve society, not just about having people see the paintings we create.

Q: If there’s anything you’d like to challenge yourself with in the future, please tell us.

There are three. The first is to create a “Japanese Art Museum”. A place with tatami mats, fusuma sliding door paintings, and a tokonoma alcove, where visitors can sit on the floor or chairs and leisurely enjoy the works. A national Japanese art museum does not yet exist. Even the Tokyo National Museum, though displaying Japanese artefacts, presents them in a European style. While the museum system itself originated in the West, making this somewhat inevitable, I want to properly convey Japanese culture not only to overseas tourists but also to the younger generation who will shape the future.

Q: The seated viewing style seems likely to foster a new way of engaging with the works. And the second?

The second is to create a system for circulating art within society. Currently, 90% of artworks produced in Japan lie dormant in warehouses and are disposed of upon the artist’s death. We should display such works in places where many people can see and enjoy them – hospitals, public facilities, corporate walls. Works with no viable placement should be properly disposed of through rituals like ceremonial burning. Frankly, art supply far exceeds demand. With the current system functioning solely through gallery sales, demand simply won’t grow.

Q: Your proposal to integrate artworks into society rather than treating them as mere commodities is truly splendid.

I very much wish to realise this. Thirdly, I propose holding competitions to promote Japan’s traditional arts. As society globalises, the world risks becoming uniformly similar wherever you go, losing its diversity. While convenient, this feels somewhat impoverished. Cultural and ideological diversity is vital for peaceful coexistence. By promoting traditional Japanese art, I hope we can contribute to safeguarding cultural diversity.

Q: What are your thoughts on the current standing of Japanese painting? Could you also share your views on its future potential?

Globally, when people think of Japanese culture, anime and manga enjoy overwhelming popularity, don’t they? It’s said their roots lie in the emaki scroll paintings of the Heian period. If traditional culture nurtured these, then surely within the paintings and calligraphy that form their origins, one can discover a unique beauty. I’d be delighted if manga and anime served as an entry point, encouraging people to take a step further and engage with Japan’s traditional culture. Recently, I held a Japanese painting workshop for children visiting from China. They were all huge fans of manga and anime. I had them try both copying the brushwork of the Bird and Beast Play Scrolls and copying the penwork of Slam Dunk. Coincidentally, they had just visited the locations featured in Slam Dunk the day before, so they were absolutely thrilled. I hope that in this way, children’s interest can expand from the manga and anime they love so much into Japan’s traditional culture.

Q: What is the essence of art that you wish to pass on to the younger generation?

I believe it is about feeling and contemplating, in one’s own way, the town and culture where one grew up through art. The world of art tends to be viewed through a very narrow lens – whether it sells in galleries or gains recognition in public exhibitions. But I want to convey that art possesses far greater breadth and potential. In the times ahead, I believe it will become increasingly important for Japanese people to understand their own culture, to practise it, and to enjoy it. However, this culture must not become a tool for conflict. What I want young people to understand is that culture exists to foster mutual respect. Rather than asserting the superiority of any particular culture, I believe it is vital to acknowledge and appreciate each other’s differences.

PROFILE

Japanese-style painter/Masatsugu Ito

Member of the Nitten (Japan Fine Arts Exhibition). Representative Director of the General Incorporated Association ART JAPAN WAGASOCIETY. While enrolled in the Japanese Painting Department at Tama Art University, studied under Japanese painters Matazo Kayama and Kiyokazu Yoneya. After completing graduate studies, created objets d’art and installations. Returned to Japanese painting following an encounter with Inten (Imperial Art Exhibition) member Itō Byōji. He began painting fusuma-e (sliding door paintings) featuring trees and flowers. Subsequently exhibited in competitions, solo exhibitions, and group shows. Currently, while belonging to the Nitten, he displays fusuma-e in public spaces such as museums, galleries, old folk houses, hotels, shrines and temples, and elderly care facilities. He aims to exhibit in places close to everyday life, seeking opportunities for people who do not usually visit museums to enjoy Japanese painting.